Last night someone I don’t know got in touch with me, politely and humbly to ask for some advice on a professional matter. This is not uncommon, and I always make time to offer what help I can; I can’t promise I’ll actually ever help, but what I’ve got is yours as much as it’s mine.

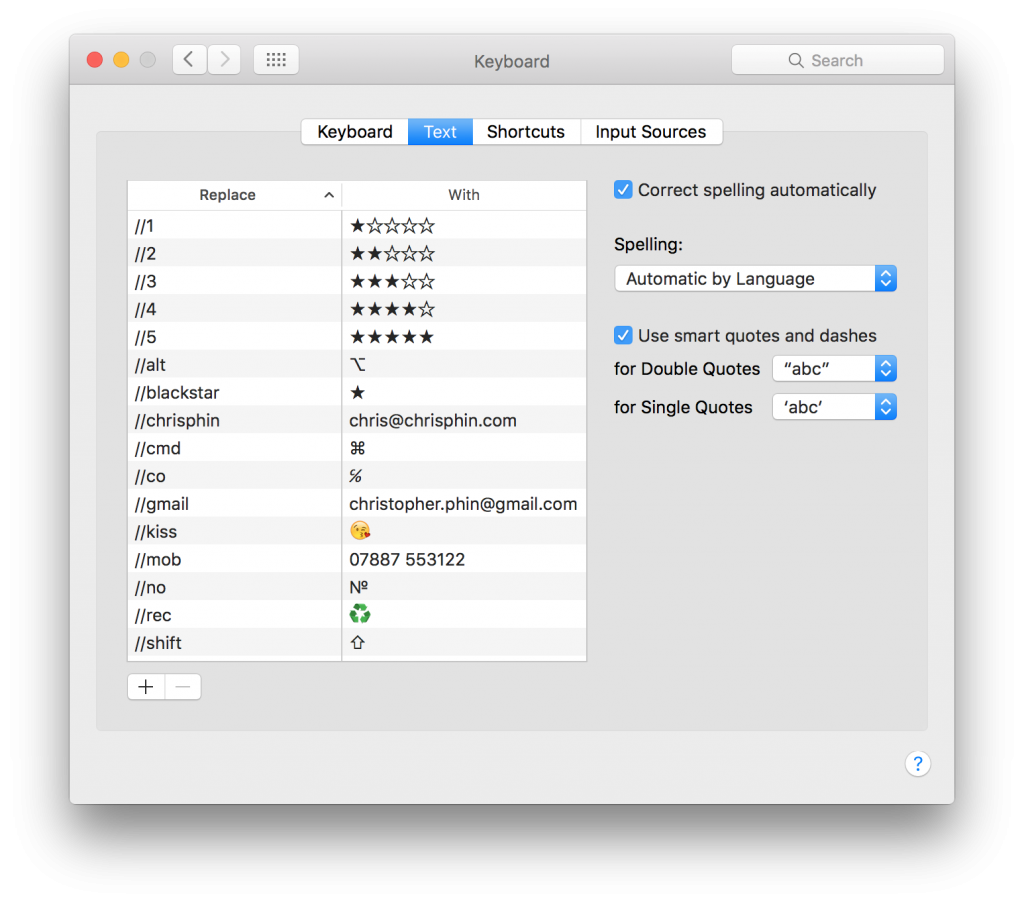

Most every time I do this I think of Susan Kare, the quite literally iconic designer best-known for creating the icons and visual feel of the original Macintosh. When I was writing my dissertation at university, on the influence of UI design on the creative process, I emailed her to ask a couple of questions. I don’t know where she was working at the time, but she would have been busy and important, and yet, magically, she replied. Two important things for me flowed from that email. The first was small and specific, but fascinating: Kare said that when designing icons, it was less important that what they represented was immediately, intuitively obvious, and more important that, once you’d learned what that icon represented – what the link is between that little grid of pixels and the action that will result when you click it – it is a strong, unbreakable semantic association.

The second was something that has only grown in the 20-some years since I dialled up the internet and polled my POP3 server to receive that email. As I have myself got busier, and more senior, and with more calls on my attention, I more appreciate the time Kare took to reply. If ever I feel like I can’t be arsed, if ever the person getting in touch is presumptuous or even rude, if ever I feel like I should be getting paid for what is in effect some free consultancy that seems to devalue the experience and knowledge I’ve built up in my career, well, then I check myself. Dear god, if Susan Freaking Kare can take 20 minutes to read and reply to an email from a green undergrad, I can carve out some time to offer the best I can to someone who asks about what mic to buy, how to get into journalism, or wants me to sense-check their CV.

I’m still besieged by impostor syndrome, and I worry I give bad advice, but so long as I caveat what I say, then surely far better that I make time to try to help, and give someone the basic courtesy of one’s attention, rather than, embarrassed, denying folks whatever I know out of my own neurosis.

I don’t, I hope, solely do this because I want folks to think of me kindly for as long or as often as Kare’s kind act has made me think of her, though I’m not a good and self-contained enough person that that doesn’t play a part in it. But rather, I remember how shocked, delighted and excited it felt that some far-off, remote figure I contacted read and replied to my message, and I want to always honour that feeling. Absolutely fuck anyone who pulls the ladder up behind them. And thanks again, Susan.