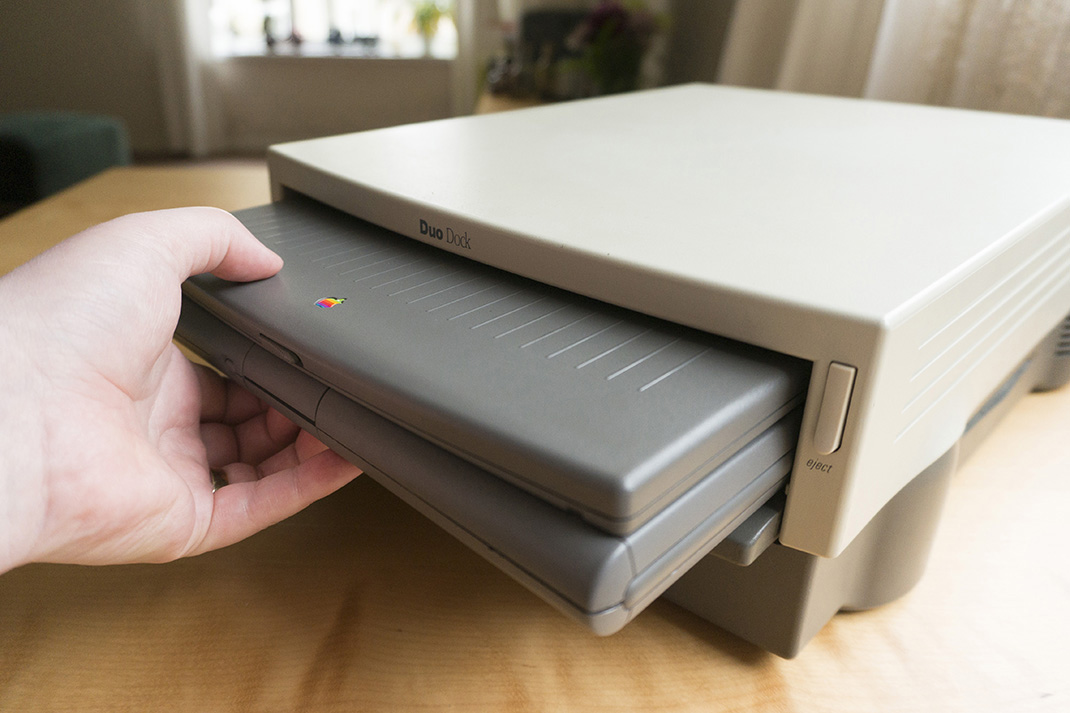

The PowerBook Duo might just be my favourite Apple computer of all time – although ask me on another day and I might say it was the Macintosh Classic, the iMac G4, the G4 Cube or something else again – and I wrote a bit about why at Macworld this week.

I picked the Duo for this week’s Think Retro because like the just-announced new MacBook, this was Apple trying to make a slim, lightweight, focussed laptop. Back when this new machine was just a rumour, though, I wrote about how Apple could reinvent the Duo concept for today, and on re-reading it while writing the Macworld piece, I was still happy with some of the ideas I proposed. Often this kind of thing leads to patently absurd, technology-for-its-own-sake-style visions of the future, but I still think my proposals sound broadly sensible, useful and feasible.

One of the obvious areas where laptops still lag is in graphics performance, and it’s at least theoretically possible to use an external graphics card hooked up over Thunderbolt – in some ways a spiritual successor to PDS – so that’s the first thing we spec into in our imaginary dock.

What’s more, with an increasing reliance on GPGPU – using a graphics card for general computing tasks – a big, meaty dedicated graphics card in the dock to augment a battery-boosting weedy graphics card inside the laptop will boost overall performance too.And while we’re about it, let’s hook up a load of internal storage as well. I’d love to see Apple put a Fusion Drive in place – a hard disk paired with a PCIe SSD, in this case inside the laptop – but leave additional bays for more hard disks. When you filled it up, you’d slot a new drive into an empty bay (a bit like the old Power Mac G5 or Mac Pro) but the clever bit is that the OS would take care of expanding the storage dynamically so you’d only ever see one drive. The speed of the SSD would keep everything fast and responsive.

When you undocked, the files on those hard disks would still be ‘there’, just greyed out, and you’d use Apple’s Back to My Mac tech seamlessly to pull it over the internet. The same tech that tells a Fusion Drive what files you regularly use in order to ‘cache’ them on the SSD means that you should have most stuff you actually need on the laptop’s internal SSD anyway. The only difference from a Fusion Drive inside an iMac is that here the hard disk is external to the laptop (inside the dock, over a Thunderbolt bus) rather than internal alongside the SSD – something you can actually do yourself today if you want to.

Indeed, one of the internal bays could be used for a dedicated Time Machine backup drive that would also work over your local network or even the internet, CrashPlan-style, when you’re undocked. And since we’re wishing, let’s finally make this the first Mac that has built-in 4G, so that the remote file grab thing works wherever you are.